By: seeker of truth

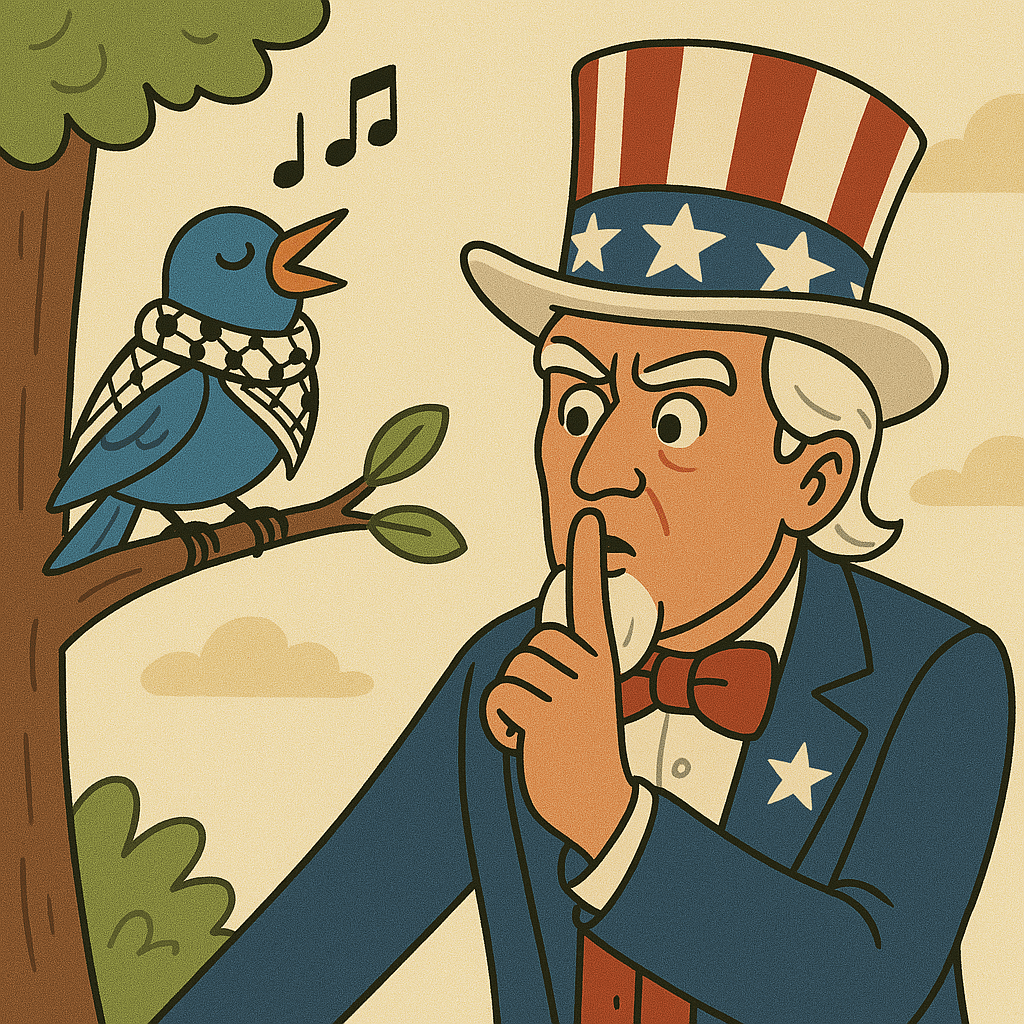

A Clash of Free Speech and National Security

A lawful permanent resident of the United States, Mahmoud Khalil, is at the center of a high-profile legal battle that pits First Amendment freedoms against national security claims. Khalil, a 30-year-old Columbia University graduate student and Palestinian activist, was arrested by U.S. immigration agents on March 8 and told his green card was being revoked for his role in campus protests. The Trump administration argues Khalil’s outspoken pro-Palestinian activism amounted to “antisemitic support for Hamas,” a U.S.-designated terrorist organization. Khalil and his defenders insist he committed no crime and was simply exercising protected speech in voicing opposition to Israel’s military actions in Gazan. The case has quickly become a crucial test of how far the government can go in deporting non-citizen protesters – and whether the First Amendment shields foreign nationals on U.S. soil from being punished for their political views.

Who Is Mahmoud Khalil and What Did He Do?

Khalil is a Palestinian-born Syrian who came to the U.S. in 2023 to pursue a master’s at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. Described by fellow students as a principled, steady negotiator, he emerged as a leader in campus protests last year advocating Palestinian rights. In April 2024, during Columbia’s “Gaza Solidarity Encampment,” Khalil helped organize demonstrations and served as a negotiator when students erected a tent camp calling on the university to divest from companies tied to Israeli occupation. He was a prominent figure in Columbia University Apartheid Divest (CUAD) – a coalition of pro-Palestinian student groups – and spoke on behalf of protesters who occupied a campus library to demand reinstatement of disciplined students. By all accounts, Khalil’s campus activism, while impassioned, did not involve violence. “He committed no crime,” one supporter noted on social media, emphasizing that Khalil’s protests were peaceful expressions of dissent.

That image contrasts sharply with how U.S. officials portray him. Days after the start of the latest Israel-Hamas war, President Donald Trump publicly linked Khalil to “pro-terrorist, anti-Semitic, anti-American activity” – without evidence, according to Khalil’s supporters. A senior Department of Homeland Security (DHS) spokesperson alleged Khalil had “engaged in concerning conduct” during a “pro-Hamas protest” on campus. In early March, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents showed up at Khalil’s university apartment and detained him. His wife, a U.S. citizen, witnessed the arrest and says Khalil expected he might be targeted for his outspokenness. Within days, he was transferred to an ICE detention center in rural Louisiana, thousands of miles from his New York community.

The Deportation Order and Legal Battle

In April, an immigration judge in Louisiana held a hearing to decide whether Khalil can be deported. The evidence presented by DHS was notably slim – “two pages. That’s it,” according to Khalil’s attorney Marc Van Der Hout. Those pages outlined Khalil’s high-profile role in campus demonstrations and accused him of espousing anti-Israel rhetoric, but no violent acts or direct links to Hamas. Still, the government insists Khalil’s very presence is a national security threat. In a memo justifying the deportation, Secretary of State Marco Rubio invoked an obscure provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act that allows the personal deportation order of any non-citizen whose presence is deemed to “have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences” for the U.S. This Cold War-era statute – rarely used in recent decades – essentially lets the State Department override normal immigration processes if a person is seen as inimical to U.S. foreign policy interests. Rubio’s memo acknowledged that Khalil’s activities were “otherwise lawful” protest protected by U.S. law, but argued they nonetheless undermine U.S. policy to combat antisemitism and to protect Jewish students from harassment.

The legal fight has unfolded on multiple fronts. While Khalil’s fate is being litigated in immigration court, his lawyers have also filed a federal civil-rights lawsuit arguing that his detention is unconstitutional retaliation for protected speech. They point out that no criminal charges have been filed against Khalil, and that officials have explicitly cited his “beliefs, statements, [and] associations” – all lawful activities – as the reason to remove him. “Neither Secretary Rubio nor any other government official has alleged that Mr. Khalil has committed any crime or broken any law whatsoever,” Khalil’s legal petition states, arguing that he is “being punished for his viewpoints.” Khalil’s attorneys have characterized the move to deport him as “astonishingly broad” and blatantly viewpoint-discriminatory, contending that immigration laws cannot be used as a “bludgeon to suppress speech that [the government] dislike[s].”

Government lawyers, however, maintain that this is not a First Amendment issue at all, but a straightforward matter of national security and immigration law. In newly filed documents, they supplemented Rubio’s foreign-policy argument with additional claims that Khalil misled immigration authorities in the past. DHS asserts that Khalil omitted key information on his 2024 green card application – namely, his prior work with a UN agency for Palestinian refugees and his leadership role in CUAD. Such omissions, they argue, amount to visa fraud and provide independent grounds for deportation beyond his speech. A DHS official accused Khalil of failing to disclose ties that “could bear on our security vetting,” though Khalil’s team calls these allegations “plainly thin” and notes that working for a UN relief agency or a British diplomatic program is hardly evidence of nefarious behavior. “There is zero support for the government’s allegations about any misrepresentation,” Van Der Hout said after reviewing the filings. In his view, the entire case against Khalil “has absolutely nothing to do with foreign policy” – it’s about punishing domestic political speech that officials disliked.

On April 11, Immigration Judge Jamee Comans issued her decision: Khalil is legally deportable under the foreign-policy provision. According to attorneys, the judge ruled that Rubio’s determination met the statutory criteria, effectively green-lighting Khalil’s removal. Khalil was not immediately expelled – his lawyers filed an emergency appeal, and the case is expected to wind its way up through the Justice Department’s immigration appeals board, and potentially into the federal courts. “Whichever side loses is likely to appeal,” Van Der Hout noted as the initial ruling came down. The high-stakes legal showdown is only beginning, with constitutional questions looming large: Can the U.S. government use immigration powers to deport someone precisely because of his political advocacy? Or does that cross a bright line set by the First Amendment?

First Amendment Protections for Non-Citizens: What the Law Says

At the heart of Khalil’s case is a novel legal question: Do non-citizens on U.S. soil have the same free speech rights as citizens, and can the government deport someone for pure political expression? The Supreme Court has long held that, yes, the First Amendment generally protects “people who are physically in the United States, regardless of their alienage”. Lawful permanent residents like Khalil typically enjoy the same core free speech rights as Americans – they can attend rallies, criticize government policies, and advocate for causes without fear of criminal punishment. “If the First Amendment means anything, it means the government can’t lock you up or deport you because of your political views,” said Ramya Krishnan, an attorney with Columbia University’s Knight First Amendment Institute. Legal scholars note that this principle has been upheld in past cases: for example, in the 1940s the Supreme Court stopped attempts to deport a West Coast labor leader over his alleged communist affiliations, affirming that “freedom of speech and of press is accorded to aliens residing in this country.”

But the government argues Khalil’s situation is different – that immigration law grants the executive branch special authority to exclude or remove non-citizens on national security grounds, even for activity that would be lawful for a citizen. The provision used against Khalil, 8 U.S.C. §1227(a)(4)(C) (the so-called “foreign policy” clause), was added during the Red Scare era precisely to deal with subversives whose presence was deemed dangerous. In theory, this power is bounded by strict criteria. Congress amended the law in the 1990s to explicitly forbid removing someone “because of [their] beliefs, statements, or associations” if those would be legal for a U.S. citizen – unless the Secretary of State personally finds that the person’s presence “would compromise a compelling United States foreign policy interest.” In other words, the government cannot normally deport someone just for their speech or associations, except in the rare case that keeping them here would gravely harm foreign policy. That sets a very high bar. Rubio insists Khalil meets it: in his view, Khalil’s campus activism on Gaza “undermine[s] U.S. policy to combat anti-Semitism around the world”, creating a compelling interest to remove him. Khalil’s attorneys strongly disagree – arguing there is no genuine foreign policy issue at all, only an effort to silence pro-Palestinian viewpoints. “By saying that attending a protest makes one a threat to American foreign policy, the administration is admitting that the Constitution is getting in the way… Something is not right there,” said Eric Lee, a lawyer for another student in a similar case.

Legal experts are divided and note that no exact precedent exists for Khalil’s scenario. The closest analogue may be the case of the “L.A. Eight” – a group of Palestinian immigrant activists whom the U.S. government tried to deport in the late 1980s for alleged ties to a militant group. Those individuals fought a decades-long legal battle, claiming First Amendment protection. Ultimately, in Reno v. American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (1999), the Supreme Court sidestepped the constitutional issue by ruling that courts lacked jurisdiction to second-guess the government’s “selective” deportation decisions. That 1999 ruling effectively insulated immigration officials from claims that they were targeting immigrants for their political affiliations – even if such targeting was alleged. Citing that case, some analysts suggest Khalil faces an uphill fight if he tries to assert First Amendment rights as a defense to deportation. “Courts might be reluctant to investigate such claims,” observed Adam Cox, a professor of immigration law at NYU, noting that judges historically defer heavily to the executive on immigration and may accept a pretextual rationale as long as some valid legal basis for deportation exists. In Khalil’s case, the government’s strategy appears to be exactly that: invoke a mix of conduct-based grounds (like purported visa fraud or “material support” of terrorism) alongside the speech-based foreign policy claim, so that even if the First Amendment issue is raised, officials can argue it’s not just about speech.

Khalil’s defenders counter that this is precisely a test case that higher courts must not duck. “There isn’t really a legal precedent for a case like Khalil’s,” said Ahilan Arulanantham, co-director of UCLA’s Center for Immigration Law and Policy, adding that the government seems to be “running headlong… right into the teeth of the First Amendment.” The Knight Institute and ACLU have similarly warned that allowing Khalil’s deportation would set a dangerous precedent, effectively carving out a free-speech exception in immigration law. They argue that even if Khalil isn’t a citizen, the Constitution’s prohibition on viewpoint discrimination should apply: the government should not be able to use deportation “as a tool to stifle entirely lawful dissent.” A federal judge in New York appeared to agree there is a serious question – in a parallel case involving Columbia student Yunseo Chung, Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald issued a temporary restraining order in late March halting Chung’s removal. In that order, the judge pointedly cautioned the government against using any alternative justifications that might “constitute a pretext for First Amendment retaliation.” Such language suggests the judiciary is at least aware of the potential constitutional violation. As Khalil’s case progresses, it could well become a landmark showdown over the limits of government power: Can the State Department’s foreign policy prerogatives trump an individual’s free speech rights? Or, as Khalil’s lawyers frame it, “is immigration being used to censor viewpoints?”

Government’s Case: Terrorism Allegations and Security Concerns

From the government’s perspective, Mahmoud Khalil is not merely a student protester – he is a national security risk. Officials have painted him as a pro-Hamas agitator whose campus activities crossed a line into extremism. In public statements, the Trump administration has explicitly linked Khalil to Hamas, a group designated as a terrorist organization by the U.S. State Department. “ICE proudly apprehended and detained Mahmoud Khalil, a radical foreign pro-Hamas student on the campus of Columbia University. This is the first arrest of many to come,” President Trump announced via the White House social media account in March. The clear message: Khalil is being held up as an example of what happens to non-citizens who show sympathy – however symbolic – with America’s enemies. Marco Rubio, the Secretary of State, has been even more blunt. “This is not about free speech. This is about people that don’t have a right to be in the United States to begin with,” Rubio told reporters, referring to Khalil and others. “You pay all this money to these high-priced schools… and you can’t even go to class. You’re afraid to go to class because these lunatics are running around… screaming terrifying things. If you told us that’s what you intended to do when you came to America, we would have never let you in. If you do it once you get in, we’re going to revoke it and kick you out.” In Rubio’s view, Khalil abused America’s hospitality by engaging in disruptive activism; thus, being a foreign national is a privilege, not a right, and it can be rescinded in the name of campus safety and U.S. interests.

Government filings in Khalil’s immigration case allege that his actions “amounted to antisemitic support for Hamas.” Specifically, the Department of Justice cites instances where Khalil allegedly led chants or made statements that officials interpret as glorifying Hamas or condoning violence. They also point to the October 2024 incidents on U.S. campuses – when the Israel-Gaza war prompted heated protests – claiming Khalil helped create a “hostile environment for Jewish students.” Although Khalil has not been charged with any crime such as incitement or material support for terrorism, the administration argues that his pattern of conduct (organizing sit-ins, leading rallies, and affiliating with hard-line anti-Zionist groups) fits the profile of someone undesirable and potentially dangerous. “The U.S. government has every right to revoke the visas or green cards of individuals who endorse or promote terrorism, and whose conduct deprives Americans of their civil rights,” insists Brooke Goldstein, a human rights attorney who focuses on antisemitism issues. Goldstein told Fox News that Khalil is “warping the First Amendment as somehow protecting his illegal conduct. It does not.” In this framing, Khalil’s protests are viewed not as peaceful dissent but as unlawful harassment – essentially an imported conflict that threatened other students. A former ICE Director, Tom Homan, echoed this view on television, arguing that “free speech has limitations” and suggesting Khalil’s campus speech exceeded those limits by “actively [engaging] in activities aligned with Hamas, a blood-soaked organization that massacres civilians.” To supporters of the administration’s crackdown, Khalil’s case is straightforward: The United States is not obligated to host non-citizens who champion extremist causes, and immigration law provides ample grounds to deny entry or status to anyone who does. “While the government can’t send foreigners to jail for saying things it doesn’t like, it can and should deny or pull visas for those who advocate for [terrorist] causes,” wrote legal commentator Ilya Shapiro, arguing that such a move poses no First Amendment problems. In short, the official stance is that national security comes first – and if that means deporting a green-card holder for chanting the wrong slogan, the law permits it.

Beyond the foreign policy statute, the government’s case against Khalil leans on the integrity of the immigration system itself. By accusing him of visa fraud/omission, officials have introduced a narrative that Khalil was not fully truthful when gaining his permanent residency. According to a DHS court filing, Khalil failed to mention on his green card application that he had worked for the British Embassy in Beirut and interned with UNRWA (the U.N. Relief and Works Agency) – experiences tied to the Middle East. He also did not list his involvement with the campus divestment coalition. To immigration authorities, these omissions could be construed as material misrepresentations if they were intentional and if the information “would have had a natural tendency to influence” the decision on his application. For instance, UNRWA has been controversial in some circles (critics allege it has indirectly abetted Palestinian militant groups), so not disclosing that affiliation might be cast as hiding a potential red flag. Khalil’s attorney responds that this is grasping at straws: “the government would have to prove any omission was willful and materially important,” which they argue it cannot. No evidence has surfaced that Khalil was asked about those specific activities or that they were disqualifying – in fact, he listed them on his LinkedIn profile publicly. To his supporters, the fraud claim looks like a pretext – a fallback way to deport Khalil if the free-speech rationale falters. “They haven’t shown he’s a threat to anyone. So now they’re combing through his paperwork hoping to find a mistake,” says one advocate with the National Lawyers Guild. Federal officials counter that it’s perfectly legitimate to charge someone with immigration violations if they discover them; they note that other activists have been caught lying on immigration forms about past arrests or memberships and later removed from the U.S. (an example is the case of Palestinian activist Rasmea Odeh, who was deported in 2017 for failing to disclose a prior terrorism conviction). Khalil, they argue, is no exception: if he wasn’t fully forthcoming, the government is entitled to strip him of the green card he obtained “under false pretenses.”

Khalil’s Defense: “This Is About Speech, Not Terrorism”

Khalil and his legal team flatly reject the notion that he posed any threat. They say he is being persecuted purely for expressing political views – views that are controversial, certainly, but well within the bounds of protected speech in America. “What is the antisemitism [they accuse him of]?” attorney Marc Van Der Hout asked rhetorically. “It is criticizing Israel and the United States for the slaughter that is going on in Gaza, in Palestine. That’s what this case is about.” In Khalil’s eyes, condemning Israeli military actions or U.S. foreign policy is not equivalent to endorsing Hamas or hatred of Jewish people; rather, it is core political speech on a matter of international concern. He notes that his activism aligned with what many human rights groups and even some U.S. lawmakers were saying during the Gaza war debate. Far from inciting violence, Khalil claims he often tried to de-escalate tensions at protests – a characterization backed by fellow organizers who praised his calm leadership. At Columbia, he was known for urging protesters to remain peaceful and focused, even as emotions ran high. In one recorded instance, when a small group of students began chanting slogans that could be perceived as glorifying violence, Khalil reportedly stepped in and redirected the crowd to chants about human rights and international law. His supporters point out that if Khalil truly “endorsed terrorism,” as the government says, it’s odd that he was never arrested by police or investigated by the FBI for any crime. Indeed, New York authorities never charged him with anything more serious than a misdemeanor trespass or obstruction during campus protests (and even those minor charges were later dropped). To Khalil and his attorneys, this underscores that he did nothing unlawful: “Khalil has been imprisoned and is being held without being charged for a crime for engaging in what should be protected free speech,” one free-speech advocate observed, noting the absence of any criminal case.

Regarding the Hamas allegations, Khalil’s defense is that the government has produced no specific evidence tying him to the militant group. He has never been a member of Hamas, never donated money to it, and never advocated violence, his lawyers say. They accuse officials of conflating criticism of Israel with support for Hamas – a leap that civil liberties groups warn chills legitimate dissent. “The claim that Mahmoud Khalil supports terrorism lacks specific evidence,” one international outlet noted in its coverage, explaining that his detention “spark[ed] free speech debates” precisely because it appeared to be based on political expression rather than any actionable wrongdoing. Khalil’s legal filings emphasize that all of his associations – with Palestinian rights groups, with Muslim student organizations, etc. – are lawful. Many of these groups explicitly condemn antisemitism and terrorism; their focus is policy change (e.g. pushing universities to divest from companies aiding the occupation). Khalil’s team has collected statements from Jewish classmates and faculty who, while they may have disagreed with him, attested that he never harassed or threatened them personally. This contradicts the narrative that he “deprived others of their civil rights.” As one Columbia professor put it, “There was a lot of heated rhetoric on both sides, but I never saw Mahmoud target or intimidate individual students.” In fact, Khalil’s advocates argue that the university protest, though disruptive, was addressing a legitimate grievance – the perceived silencing of pro-Palestinian voices – and Khalil’s role as a negotiator helped peacefully end the encampment standoff with campus administrators.

On the immigration fraud issue, Khalil flatly denies lying or hiding anything material. He did not think to list every short-term internship or activism affiliation on his green card application, his lawyers explain, because those forms typically ask for employment and organizational memberships “relevant” to eligibility or security. Khalil had undergone extensive vetting when he was granted refugee status in Lebanon and again when adjusting status in the U.S., and nothing in his background – including his work with the British Foreign Office and the UN – raised flags at the time. “Zero to do with the foreign policy charge. And there is zero support for… any misrepresentation,” Van Der Hout said, arguing that the government’s eleventh-hour document dump about Khalil’s résumé is a sign of a weak case. Khalil’s attorneys note that involvement in political activism, like CUAD, is not a disqualifier for a green card, so failing to mention it cannot be “material.” They accuse the administration of moving the goalposts – after initially justifying Khalil’s arrest on national security grounds, when pressed in court they scrambled to find any technical violation to justify deportation. This shifting rationale, they argue, betrays the true motive: Khalil is being targeted for his speech. Emails obtained in discovery show that federal agents were monitoring Khalil’s Twitter posts and speeches at rallies, not digging through his old job records, in the lead-up to his arrest. “It was exclusively about what he was saying and who he was saying it with,” said one of Khalil’s immigration attorneys, “and only once we challenged them did they start talking about his visa forms.” Such sequencing bolsters Khalil’s claim of retaliatory intent.

Perhaps most poignantly, Khalil’s family circumstances highlight what is at stake for him. Since 2022 he has been married to an American citizen, and the couple is expecting their first child. In a court affidavit, Khalil’s wife described the profound stress of watching her husband “disappeared” into ICE custody for weeks with little information. “I keep asking why,” she wrote, “how can this happen in America – to arrest someone from our home simply because of a protest?” She noted that Khalil’s absence means he might miss the birth of their baby, and that if he’s deported to the Middle East he could be separated from his young family for years or forever. These human stakes underscore a broader point Khalil’s defenders make: deportation is a severe punishment, akin to banishment, and imposing it for expressive conduct runs counter to American values of liberty. As one prominent activist, Medea Benjamin, told an international newspaper: “The U.S. has always portrayed itself as a beacon of free speech — but what we’re seeing now is the exact opposite. Arresting student Mahmoud Khalil simply because they didn’t like what he said is a terrifying precedent.”

Protest and Public Outcry

Khalil’s arrest and detention have galvanized a nationwide protest movement that extends from city streets to social media feeds. In New York, just days after his ICE detention, hundreds of people gathered outside the federal courthouse and at other symbolic sites to demand Khalil’s freedom. Demonstrators held signs declaring “Free Mahmoud! Free Speech!” and “Hands off our students!”, linking his case to a broader defense of civil liberties on campus. Chants of “From NYC to Palestine, free free Mahmoud!” echoed as activist groups like the Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) and local chapters of Students for Justice in Palestine rallied in his support. “We will continue to stand on the right side of history – Free Rumeysa Oztürk & Free Mahmoud Khalil!” PSL’s national organization tweeted, pairing Khalil’s cause with that of another student (Oztürk, a Tufts University graduate student) who was detained by ICE after writing a pro-Palestinian op-ed. This emerging coalition sees the crackdown on pro-Palestinian protesters as a coordinated campaign to silence dissent. Indeed, the hashtag #FreeMahmoudKhalil began trending on Twitter (X), and an online petition demanding his release gathered tens of thousands of signatures within a week. Free speech organizations across the ideological spectrum – from the ACLU on the left to the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) on the libertarian right – have sounded the alarm. “Citizenship won’t save you,” one NPR headline warned, as even U.S. citizens realize that if lawful residents can be whisked away for their speech, the climate for dissent darkens for all.

On social media, the case has been intensely debated, with sharply divergent narratives. Progressive and pro-Palestinian voices frame Khalil as a victim of authoritarian overreach. They describe his detention as part of a “fascist attack… eroding dissent, free speech, democracy”. Many point to the irony of a country that champions free expression abroad locking up a student for protesting war. “The entire world is appalled by this flagrant violation of freedom of speech!” one supporter wrote in reply to a State Department post. Others note the relative silence from some self-described free speech advocates: “It’s kinda crazy that all these free speech clowns and campus conservatives have nothing to say about Mahmoud Khalil… being arrested and possibly deported. He committed no crime,” one commentator tweeted in frustration. This sentiment highlights how Khalil’s case has become a politicized litmus test – with some accusing the right of hypocrisy for defending offensive speech on campus unless it’s pro-Palestinian. Activists like Moustafa Bayoumi and Heba Gowayed have written pieces titled “Trump is using Mahmoud Khalil to test his mass deportation plan,” arguing that the administration is leveraging fear of Hamas to push through a much broader assault on political activism.

On the other side, conservative and pro-Israel groups applaud the government’s hard line. They argue that what’s at stake is not free speech but public safety and moral clarity. On X (Twitter), some users celebrated Khalil’s predicament with undisguised glee. “Mahmoud Khalil the pro-violence agitator/protester for Hamas is now free! He’s free to go back to his country to protest and wreak havoc,” one post sneered, effectively telling Khalil to “good riddance”. Another critic insisted Khalil “took over a library… This is not speech it’s conduct and silencing other people’s speech. …He needs to go. He’s anti-free speech and anti-American.” This view depicts Khalil not as a peaceful protester, but as a bully who trampled on the rights of Jewish students – thus forfeiting any claim to First Amendment protection. Right-wing pundits have used terms like “campus jihadi” and “terror sympathizer” to describe him, lauding ICE for, as one put it, “finally doing something about these antisemitic lunatics on campus.” Even some mainstream voices who normally champion free speech have wrestled with the case. For example, an op-ed in The Washington Post argued that “The Khalil case isn’t about speech, it’s about immigration law,” suggesting that whatever one’s view of Khalil’s protests, the law clearly allows a non-citizen to be removed for causing turmoil.

Meanwhile, elected officials and civil society leaders have weighed in. A group of Democratic members of Congress from New York issued a joint letter calling for Khalil’s release, stating that “using immigration enforcement to retaliate against protesters sets a dangerous precedent.” On the other hand, Republican lawmakers have largely backed the administration. At a House hearing, a GOP congressman held up a poster of one of Khalil’s tweets and asked a DHS official why Khalil hadn’t been deported “yesterday,” given his “anti-American propaganda.” The polarization is striking: to one camp, Mahmoud Khalil is a canary in the coal mine for free speech – an indicator of creeping authoritarianism – while to another, he is an object lesson that non-citizens who “misbehave” should expect swift expulsion.

Broader Implications for Free Speech and Immigration

Beyond one graduate student’s status, the case of Mahmoud Khalil raises profound questions about free speech rights for non-citizens in the United States. America has long been a haven for political refugees and dissidents, premised on the idea that here, unlike in authoritarian regimes, one will not be punished for speaking out. Khalil’s deportation fight has many asking: Does that promise apply equally to all who live here, or only to citizens? The chilling effects are already being felt among immigrant communities. According to NPR, Secretary Rubio has boasted of revoking over 300 visas from foreign students and scholars in recent months who joined protests or made statements deemed sympathetic to Hamas. International students from the Middle East (and beyond) have reported increased scrutiny – and a growing fear that voicing certain opinions could jeopardize their studies or careers. One PhD student from Hong Kong, a U.S. green-card holder, told reporters he has begun scrubbing his social media of any controversial political posts, worried that “what I say online might be used against me when I re-enter the country.” “I don’t join protests now,” he said. “I feel like it’s a stupid thing [to do]… I’m being compliant before the thing even hits me.” Such self-censorship is exactly what free speech advocates feared. If non-citizens – even those with legal permanent residency – believe they can be “disappeared” by ICE for attending a march or signing a petition, many will simply steer clear of any activism. And as one commentator noted, “the First Amendment rights of citizens are intertwined with those of non-citizens – if the government can silence one group, it sets a precedent to silence others.”

Historically, the U.S. government has at times wielded immigration law as a tool against political undesirables – from anarchists and communists in the early 20th century to human rights critics more recently. But in the modern era, explicit deportations for pure speech have been exceedingly rare. That’s why Khalil’s case is often described as unprecedented. “They’re trying to create essentially a foreign policy authority to deport green card holders [for their speech],” observed Ahilan Arulanantham, noting that the administration’s broad reading of the law could open the door to many more such actions. Today it is pro-Palestinian activism in the crosshairs; tomorrow it could be another issue. In fact, one striking example emerged alongside Khalil’s: Óscar Arias Sánchez, the former president of Costa Rica (and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate), had his U.S. visa suddenly revoked in 2025. The stated reason was his engagement with China years ago, but Arias publicly speculated it might be retaliation for his outspoken criticism of President Trump. “I have to imagine that my criticism of President Trump might have played a role,” Arias told NPR, after likening Trump to a “Roman emperor” in a social media post. If even a former head of state isn’t immune to visa cancellation over speech, activists note, it underscores that immigration status is increasingly being used as leverage to enforce ideological conformity.

Civil libertarians argue that such practices erode the open democratic culture that the First Amendment is meant to foster. The Knight First Amendment Institute pointedly wrote, “the First Amendment prohibits government officials from subjecting an individual to retaliatory actions for their speech.” They are preparing for a possible constitutional showdown. Should Khalil’s case advance to federal court on First Amendment grounds, it could set a major precedent. A ruling in Khalil’s favor could firmly establish that lawful permanent residents cannot be deported for pure political advocacy, reaffirming the U.S. as a safe haven for dissent. Conversely, a ruling siding with the government might effectively give the executive branch a green light to police the speech of immigrants under a national security rubric.

Meanwhile, immigrant rights groups warn of a “slippery slope”. They note that millions of Americans live in mixed-status families (with U.S. citizens, green-card holders, visa holders all under one roof). If one member of the family – say a student or a visiting scholar – has to fear punishment for political speech, the entire family may self-censor. Over time, this could shrink the space of public debate, especially on contentious foreign policy issues. Already, university administrators have reported international students avoiding campus discussions or student club activities related to Middle East politics, not wanting to be on any “list.” Professors, too, are concerned: will inviting a controversial speaker or allowing a heated protest now risk their foreign students’ futures? Academic freedom and open discourse at universities could suffer, some educators argue, if the government actively monitors and penalizes the political engagement of students from abroad.

As for Mahmoud Khalil himself, he remains in legal limbo – free on bond after seven weeks in ICE detention, but under the shadow of deportation. “He hasn’t been deported yet,” one social media commenter noted, “but it’s funny how you Americans love free speech and always talk about it… Khalil organized protests in a country that’s not his own, and since he’s not American, well, that’s why he’s getting deported.” That sardonic observation captures the crux of the debate: is the freedom to dissent a human right that the U.S. extends to all within its borders? Or is it a privilege of citizenship, with outsiders voicing “unpopular” views sent packing? The Khalil case may force an answer.

One thing is clear: the stakes are far-reaching. As Khalil awaits the next round of appeals, student groups continue to demonstrate on his behalf, and legal experts on both sides prepare for a protracted fight. “If Trump can deport Mahmoud Khalil for exercising his First Amendment right to free speech – Trump can deport anyone,” a concerned observer tweeted. On the other hand, those cheering the deportation effort argue that expelling Khalil will “set an example” to deter campus extremism. This collision of viewpoints – free expression versus security, inclusivity versus exclusivity – strikes at the heart of American identity. The final outcome, whether Khalil is allowed to stay or forced to leave, will reverberate as a defining marker of how the United States balances liberty and safety in an age of polarization and fear.

Leave a comment